Nov 15 2013

Advanced computer codes are helping scientists reimagine how they might initiate a fusion reaction in the center of a tokamak, a doughnut-shaped experimental vessel. These simulations are also shedding new light on complex phenomena in magnetic fields.

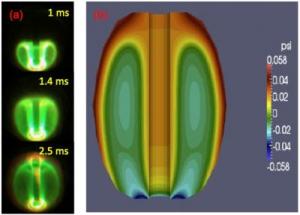

(a) This is a sequence of visible fast camera images of a CHI discharge inside NSTX. The top image shows the expansion of the CHI discharge one thousandth of a second after it is initiated. As shown in the third frame, within three thousandths of a second the plasma has fully filled the vessel; (b) the magnetic structure of a bubble in NSTX as simulated by the NIMROD code. Credit: Fatima Ebrahimi, Roger Raman, and Edwin Bick Hooper

(a) This is a sequence of visible fast camera images of a CHI discharge inside NSTX. The top image shows the expansion of the CHI discharge one thousandth of a second after it is initiated. As shown in the third frame, within three thousandths of a second the plasma has fully filled the vessel; (b) the magnetic structure of a bubble in NSTX as simulated by the NIMROD code. Credit: Fatima Ebrahimi, Roger Raman, and Edwin Bick Hooper

Plasma confinement devices based on the tokamak concept rely on a solenoid that runs through the center of the device to generate the initial current. But solenoids have a limited pulse length and cannot sustain the initial current indefinitely in a steady-state reactor. Finding a way to eliminate the solenoid would remove a large component from the center of the tokamak, make the device simpler and less expensive, and allow the freed space in the center to be used to optimize the tokamak and make it more efficient.

Now, advanced computer modeling with the NIMROD code—code specifically designed to facilitate these simulations—has begun to describe the mechanism behind a magnetic structure that could replace the solenoid to start the initial current. This modeling simulates an enormous magnetic bubble that carries 300,000 amperes of current, or 1,500 times the amount that flows into a home.

Researchers conducting experiments on the National Spherical Torus Experiment (NSTX) at the U.S. Department of Energy's Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) have produced the actual bubble through a method known as transient Coaxial Helicity Injection (CHI). Originally developed on the much smaller HIT-II device at the University of Washington, the method has been improved on the NSTX spherical tokamak, which has a volume 30 times larger.

CHI uses a process called magnetic reconnection to create the bubble. This process takes place when magnetic field lines break apart and reconnect with a burst of energy. The type of reconnection that occurs during transient CHI experiments in NSTX is similar to the process that produces solar flares—the magnetic strings, or filaments, ejected from the surface of the sun. These experiments also represent the first-ever occurrence of forced magnetic reconnection during an experiment on a large-scale fusion facility. CHI creates a bubble inside the NSTX by driving currents along magnetic filaments in the plasma. The sequence of camera images in figure 1a, below, shows the bubble being generated in the lower part of NSTX and expanding to fill the entire vessel.

The NIMROD simulations conducted by the research team shed important light on the mechanisms at work in the magnetic bubble, clarifying what happens at various stages in the ultrafast phenomenon:

- First, magnetic forces arising from the current on the surface of the filaments overcome the rubber-band-like tension that could reverse the strings' expansion. This allows the strings to expand and fill the vessel.

- Second, when the current is suddenly turned off, the expanded strings seek a stable configuration.

- Third, the simulations show that new forces then take over. These bring the magnetic strings in the lower part of the NSTX vessel closer together until they reconnect and generate a magnetic bubble.

- Finally, the simulations are now starting to identify the different parameters needed to generate a high-quality magnetic structure.

This work is also related to some universal aspects of magnetic reconnection physics, including the processes that occur on the surface of the sun. These exciting results are the subject of an invited talk and other supporting presentations at this meeting. CHI research on NSTX is a collaboration between researchers from Princeton University, the University of Washington, the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Source: http://www.aps.org/