With industrialization gaining momentum in the United States and new construction sprouting up everywhere shortly after the end of the Civil War, there was a growing need for better ways to test the materials utilized in machinery and buildings.

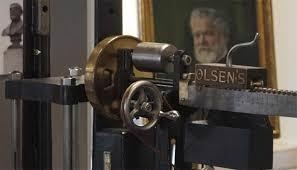

Image Credit: Tinius Olsen

Engineers acknowledged the lack of reliable information on the properties of materials; “The art of construction….is involved in mystery and obscurity,” noted Van Nostrand’s Engineering Magazine.

“The knowledge of materials is at present absolutely empirical. Before the constructor makes use of either a new material or an old one in a new form, the only safe method is to experiment.”

However, without a way to test the strength of materials prior to utilization, these experimental results were likely to take the form of building collapses or explosions.

From the 1850s onward, numerous devices for testing materials had been developed, but until 1880 the goal of a truly universal testing machine proved elusive.

This was when Tinius Olsen, an unemployed Norwegian immigrant, devised and patented the now famous Little Giant.

Now there was finally a machine for transverse, tensile and compression testing, together in a single instrument. Olsen’s mechanism was to become the ancestor of all testing machines subsequently created around the globe.

The Tinius Olsen Testing Machine Company Inc produces innovative, leading materials testing solutions to this day and the company celebrated its 140th year of continuous operations in 2020.

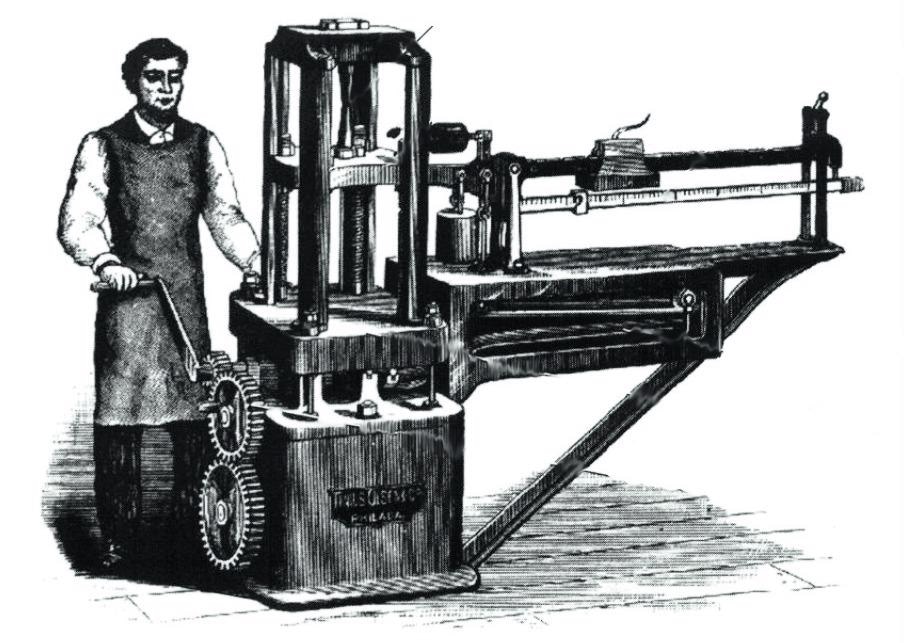

The Little Giant of 1880. Image Credit: Tinius Olsen

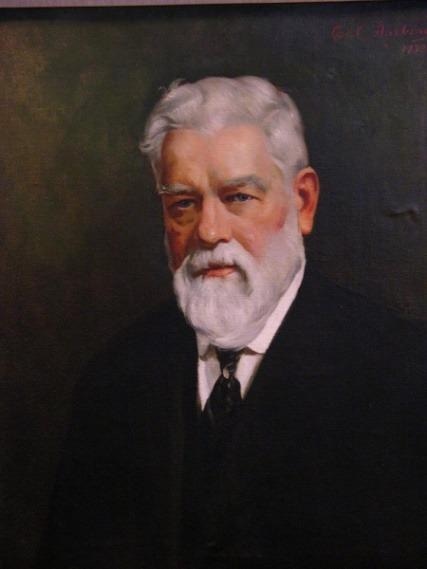

Olsen was born in 1845 in Kongsberg, Norway. He was one of eight children of a wooden gun stock maker. He graduated at the head of his class from the Horten Technical School in 1866 and became the foreman of the machine department at a large naval machine shop.

Olsen did not like this job and left for America after trying to find work in Newcastle, England. In August 1869, 24-year-old Olsen arrived in Philadelphia and found employment as a designer with William Sellers and Co.

Olsen began attending Sunday Bible classes at the local Lutheran church, where he met the proprietors of a small scale-making workshop, the Riehlés brothers. They had received an urgent request for a machine to test the strength of a boilerplate.

At the time, no such device existed, and weak plate materials often caused boiler explosions, particularly on steamboats that were traveling up and down the Mississippi.

The brothers asked him to produce engineering drawings for the instrument, and Olsen designed and drew precise plans for the first boilerplate tensile testing machine in his spare time; it had a capacity of 40,000 lbf.

Manufactured by the Riehlé brothers, the new device proved a success, and soon there was a demand for a much bigger model.

Olsen was asked to take charge of the workshop, and in 1872, he became director of the Riehlés plant. He helped establish the firm as a manufacturer of both testing machines and springs in his eight years there.

His pioneering contributions to the emerging field of materials testing included vertical and horizontal machines for materials, which were utilized in locomotive boilers, bridge construction and other industrial goods.

The Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876 exhibited a number of these machines. However, the patents were still the property of his employers.

All this inventiveness did not go unnoticed. In 1879, the Committee on Science and the Arts of the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia’s prestigious center for scientific study and information, appointed a subcommittee to investigate Olsen’s testing machines.

The machines were “convenient to operate, properly proportioned and handsomely designed and accurate withal”, according to the committee’s report, perhaps it was this praise that prompted Olsen to ask the Riehlés to make him a partner.

They refused, and in late 1879 he was told that his services would terminate at the end of the year. However, Olsen was full of ideas for a revolutionary device: a universal testing machine.

He began making the drawings for his new machine with the support of his wife, Charlotta, one of the first Scandanavian-American women to earn a degree in medicine. Olsen submitted an application to patent a ‘new and useful improvement in testing machines” on Feb 6th, 1880. Patent no. 228,214 was granted on June 1st, 1880.

Most tests of materials needed different machines in those days, and each was dedicated to a single testing function.

Olsen’s Little Giant could accurately perform transverse, tensile and compression tests in one instrument, which was housed in a single frame. The device was not expensive, and it was compact and simple to operate.

Image Credit: Tinius Olsen

Olsen explained in his patent application that testing machines previously wasted most of the applied power in friction or that they had difficulty in exerting pressure on the sample.

He proposed to decrease the power absorbed by friction, build the weighing levers to be more compact, supply an automatic motion for the weight on the beam and supply a “sensitive measuring apparatus for measuring the distortion of the specimen, as well as an apparatus for graphically recording and illustrating the same distortion.”

The Little Giant was a vertical model, with the forces applied to the specimen to be tested from above and below. Upper and lower loading crossheads contained grips that pulled the specimen apart or held and crushed it as the operator turned a handle attached to a system of gears.

For tensile testing, the specimen was held between the upper and lower crossheads as the lower one pulled down, and the stationary upper crosshead transmitted the force through the vertical frame to a weighing table below it.

In turn, this table transmitted the force to a weighing beam through levers, where the load was quantified. The specimen was placed below the lower crosshead for compressive testing; this pushed down on the specimen that, in turn, was pushed down on the weighing table.

In transverse testing, the specimen was again between the weighing table and the crosshead. Here the load was focused on the center of a longer specimen, like a steel girder or a piece of cast iron.

His load frame design was not Olsen’s only new idea. His loading and weighing systems were also enhancements over previous practice. His weighing levers dramatically reduced space requirements, and his system of gears and screws could apply controlled forces to the test specimen.

An electric motor as an optional attachment could be automatically employed to move the poise or weight on the beam without the operator having to touch it at all. The Little Giant supplied a graphic record of its measurements in addition to adding greater precision.

Damage protection was supplied by rubber cushions and springs, which obviated what had been a difficult problem - when a specimen broke, testing machines were frequently damaged.

Olsen’s device has been called the basis of all testing machines because of all these innovations.

Olsen’s wife talked him into going into business for himself after an established Philadelphia firm declined to take on the new product.

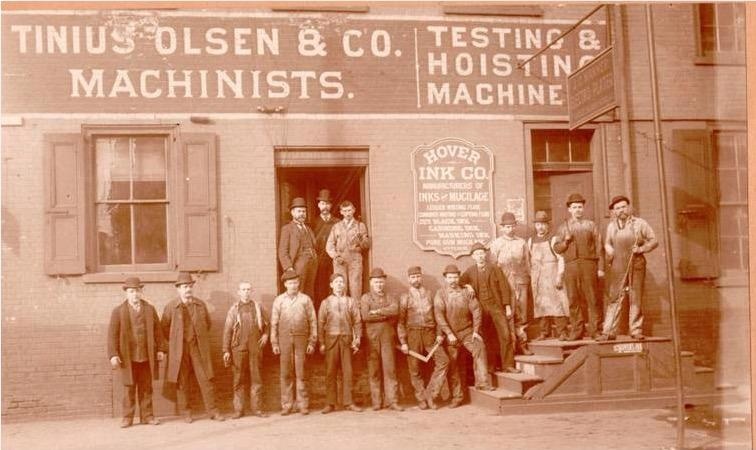

The two of them only had a few thousand dollars, but he managed to establish his workshop, Tinius Olsen & Co., at 500N 12th Street in Philadelphia. Soon he was taking business away from the Riehlé brothers, his old employers.

Olsen refused to go into debt but his wife was so determined to see the machine exhibited that she pawned her diamond rings to raise funds to send the Little Giant to industrial expositions in Atlanta and Cincinnati in 1881. The machine won gold medals at both shows.

By the following year, Olsen had an order for the first 200,000 lbf testing machine ever made, and he also built a machine to test the tensile strength of feathers as an example of his diversity.

Workers outside the first Tinius Olsen & Co factory at 500 North 12th Street, Philadelphia c. 1890. Image Credit: Tinius Olsen

For decades thereafter, Olsen continued to make innovations in the testing machine field.

The Franklin Institute awarded him the Elliot Cresson Gold Medal for his autographic testing machine in 1891, which produced an easily interpreted, permanent record of stress-strain results.

The federal government ordered a 10 million pound capacity machine in 1908, which, until the middle of the century, remained the largest testing machine in the world.

Other honors came his way over the years, including a medal from the king of Norway.

Olsen retired from the company in 1929 and died in 1933.

The company he started in 1880 is still run by his descendants and is now in its fifth generation.

What started out as a small business with little investment capital in Philadelphia now has offices and manufacturing plants around the globe, including India, the UK and, most recently, China.

This information has been sourced, reviewed and adapted from materials provided by Tinius Olsen.

For more information on this source, please visit Tinius Olsen.