In this interview, industry experts Mustafa Kansiz and Craig Prater explain how recent laser-scanning submicron IR (O-PTIR) innovations enhance chemical imaging, accelerate microplastics analysis (especially the <10 micron and submicron fractions), and expand multimodal spectroscopy capabilities across life science and materials research.

To begin, can you explain the main limitations of traditional vibrational spectroscopy methods and how they set the stage for O-PTIR?

Dr. Mustafa Kansiz: Traditional direct IR techniques, such as FTIR or Quantum Cascade Laser (QCL) based systems, are fundamentally diffraction-limited in the IR, which restricts spatial resolution to 10-15 microns in practice. Note, this is not to be confused with pixel size, which is often much smaller, but does not equate to achievable spatial resolution.

Sample preparation can also be difficult because many measurements require thin sections in transmission. Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) avoids thickness constraints, but the required contact poses a risk of damaging samples and/or the ATR crystal.

Another major issue is dispersive and scattering artifacts. Spectra can vary not only because of chemistry but also because of particle shape, size, and morphology, making interpretation and library matching challenging.

Raman offers better spatial resolution but often suffers from autofluorescence, limited sensitivity (especially for the smaller particles), slower hyperspectral mapping, and a risk of photodamage depending on laser power.

Furthermore, long alky chains, as often found in stearates, detergents and similar molecules, can easily be mis-identified as polyethylene (PE). This is due to the fact that Raman is very sensitive to non-polar groups, like long carbon chains, but is far less sensitive to the differentiator polar head groups on these sorts of molecules.

Additionally, pigmented polymers can be challenging for Raman because of resonance Raman signals from the dyes swamping the polymer signals and/or the pigments absorbing the excitations wavelengths and causing easy sample burning, e.g. red or dark polymers with 532nm excitations.

Another technique sometimes used is fluorescence imaging, which provides excellent specificity but no broad chemical characterization and certainly no polymer identification.

All of these limitations make it challenging to obtain chemically reliable information at small scales, which is why submicron IR with O-PTIR has become so transformative.

How does O-PTIR work, and what advantages does it bring over traditional IR and Raman techniques?

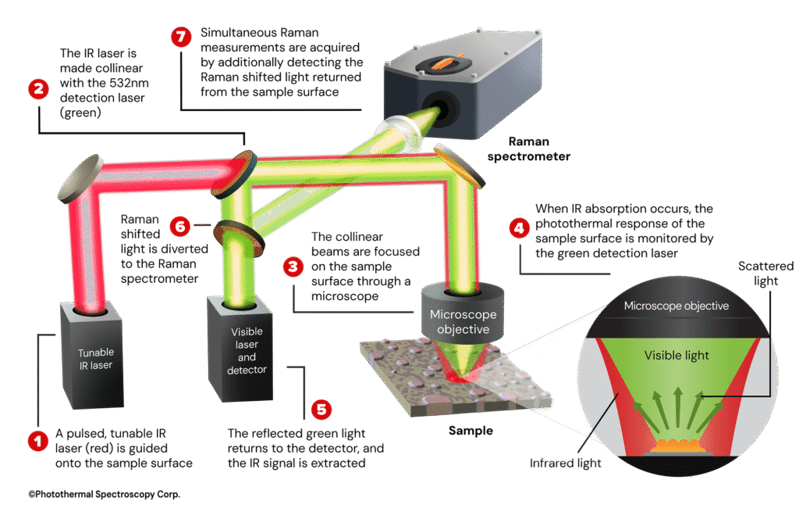

Dr. Mustafa Kansiz: O-PTIR is a pump-probe technique that excites the sample with a widely tunable infrared laser (like a QCL) and probes it with a tightly focused visible beam (typically 532nm or 785nm). When the infrared light is absorbed, the sample heats and expands slightly, creating a refractive index change that modulates the reflected visible beam. We detect this modulation by changes in reflectivity of the visible probe beam and reconstruct what is essentially a pure infrared absorbance spectrum, even though we measure in reflection mode.

The short wavelength visible beam gives us sub-micron, even up to <500nm, wavelength-independent spatial resolution that exceeds Raman resolution. Because the probe beam is Raman-grade, we can also obtain simultaneous IR and Raman spectra from the same spot, at the same time with the same resolution.

Image Credit: Photothermal Spectroscopy Corp.

What kinds of samples and imaging configurations can O-PTIR support?

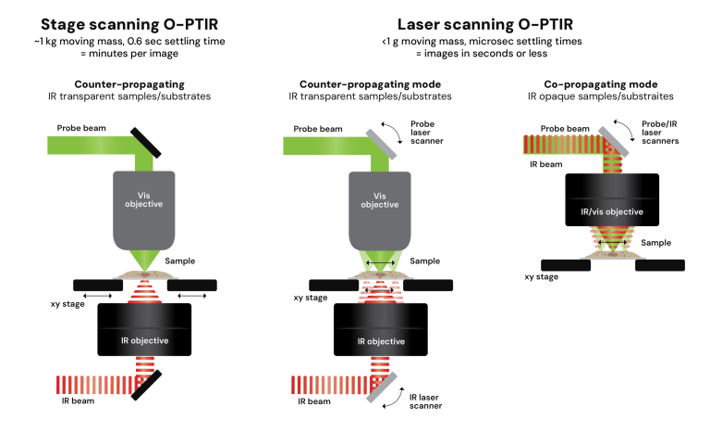

Dr. Mustafa Kansiz: O-PTIR is extremely flexible. We can operate in so called “co-propagation mode” where both the IR and visible probe beam are delivered from the top with typically reflection mode, or in "counter-propagating mode", where IR enters from below, and the probe enters from above.

Counter-propagating mode allows the use of high-NA visible objectives giving the best spatial resolution (<500nm), and best IR and Raman spectral sensitivity (SNR). It also enables imaging of cells in water through the use of water dipping or oil immersion objectives, which is not possible with direct IR techniques such as FTIR and QCL based systems. We routinely image cells, tissues, polymers, microplastics, thin films, hydrated samples, and even live biological specimens.

Can you describe how fluorescence imaging integrates with O-PTIR and why this matters?

Dr. Mustafa Kansiz: Adding widefield fluorescence has been a major breakthrough. Users can perform traditional fluorescence imaging on either labelled samples or simply using a samples' inherent autofluorescence, and then immediately collect O-PTIR spectra and chemical maps without changing objectives or repositioning samples. This enables fluorescence guided chemical interrogation.

Fluorescence provides spatial context with excellent specificity, and O-PTIR adds label-free biochemical characterization that fluorescence alone cannot provide.

Interview with Dr. Mustafa Kansiz

Video Credit: Photothermal Spectroscopy Corp.

What are some of the standout application areas where O-PTIR is having the biggest impact?

Dr. Mustafa Kansiz: We see significant interest and growth across many application areas.

In life science research, O-PTIR is providing new insights into protein structure, neurodegeneration studies, lipid metabolism, and even hydrated tissue imaging. In pharmaceuticals, we can characterize drug formulations on glass slides, analyze subvisible particles, and perform rapid, automated chemical identification.

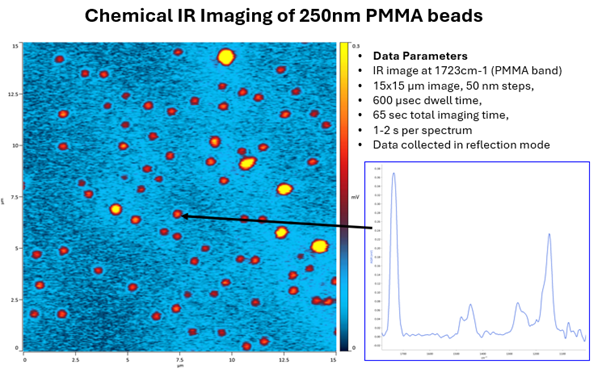

Microplastics is also an important application area as research interest deepens into the smaller fractions, especially the few micron and submicron (nanoplastics) where O-PTIR is unique in its ability to characterize particles to <500nm levels and obtain high-quality spectra, including simultaneous IR and Raman for confirmation.

Image Credit: Photothermal Spectroscopy Corp.

In fact, any organic particulate measurement is ideal. From the already mentioned microplastics (nanoplastics) to pharmaceutical formulations (e.g. Orally Inhaled and Nasal Drug Products, OINDPs) to visible and sub-visible contamination of protein aggregation in biologics in biopharma, through to environmental aerosols characterization.

Furthermore, we’ve seen ongoing interest in semi-high tech manufacturing failure analysis for organic contaminant characterization and materials science research.

Turning to the new system, what motivated the development of the mIRage-HSi laser-scanning platform?

Dr. Craig Prater: Traditional O-PTIR instruments rely on mechanically scanning the sample stage, which has a large moving mass. Even with optimized hardware, settling times limit us to minutes per image. Laser-scanning O-PTIR replaces stage movement with high-speed galvo mirrors that synchronously scan both the IR and visible beams. These mirrors have extremely small moving masses and settle in microseconds, enabling a speed increase of >30x.

The result is our new laser-scanning O-PTIR platform, the mIRage-HSi, which performs hyperspectral imaging in minutes, and single-wavelength imaging in seconds.

Image Credit: Photothermal Spectroscopy Corp.

How does the laser-scanning system maintain signal-to-noise at such high acquisition speeds?

Dr. Craig Prater: At low frequencies, lasers exhibit 1/f noise, which increases the noise floor. At the higher modulation frequencies used in laser scanning, that noise essentially disappears. The shorter pixel dwell times alter the heating dynamics, allowing us to achieve stronger photothermal modulation. We can also use higher laser powers without causing sample damage because we are not dwelling on any pixel for long. These combined effects allow us to maintain an excellent signal-to-noise ratio even while scanning thirty times faster.

How do you ensure the IR and probe beams stay perfectly overlapped during fast scanning?

Dr. Craig Prater: Beam synchronization is essential. We developed automated calibration routines that map and correct non-linearities in the scanning system. The software then applies these corrections dynamically, so the IR and probe beams remain precisely overlapped across the scan field. Users simply run an automated alignment step at the beginning of a session. After that, the system maintains beam overlap without manual adjustment.

What capabilities does the mIRage-HSi introduce for particle analysis and microplastics research?

Dr. Craig Prater: When it comes to particulates analysis, with the new laser-scanning platform there are three key enhancements which will have an important impact on speed and data quality.

Firstly, with laser scanning O-PTIR, we will be able to precisely, and on a per-particle basis, determine the exact center of the particle before spectral collection to support the best spectral quality on even small particles. This becomes critical when measuring very small particles (less than a few microns and certainly into the hundreds of nm range) since with stage travel alone, whilst one can detect the location of particles with regular visible or fluorescence imaging, driving to these particles, perhaps numbering hundreds or thousands, will introduce slight mechanical stage drive imprecision, which for the very small particles, could mean the difference between a good spectrum and a poor spectrum.

Secondly, with laser-scanning O-PTIR comes ultra-fast single frequency imaging, allowing the system to image and identify particles hundreds of nanometers in size in seconds.

Finally, because the mIRage-HSi can rapidly acquire multi-wavelength images, we can discriminate plastics from interferents like carbonates before spending time on spectral acquisition which significantly improves time to data.

All of these capabilities are automated in through our “FeaturefindIR” routine, which finds the particles (through segmentation of visible, fluorescence or chemical images), generates particle morphology data (like shape and size) and performs a chemical identification using built in (or user editable) spectral libraries. We also support simultaneous IR and Raman library searching from a single particle.

What additional multimodal or emerging techniques does the mIRage-HSi support?

Dr. Craig Prater: The platform supports spontaneous Raman, widefield fluorescence, laser-scanning confocal fluorescence, and photothermal stimulated Raman scattering, PT-SRS.

Photothermal stimulated Raman scattering (PT-SRS) uses stimulated Raman excitation but instead of detecting the Near IR SRS laser photons, it relies on the deposited heat from Raman excitations process, which induces a subtle photothermal modulated heating, which we detect with a separate, probe beam.

PT-SRS when coupled with smaller, robust and easier to use pulsed NIR fiber lasers, provide for ultra-fast tuning (10’s of msec) and ~10x improvement in sensitivity whilst also removing the need for two immersive objectives, which otherwise limit the samples to be essentially in coverslip sandwiches. All this provides highly sensitive Raman contrast, enabling fast imaging of lipids, proteins, and dynamic biological processes.

About Mustafa Kansiz

Dr. Mustafa Kansiz, Director of Product Management and Marketing at Photothermal Spectroscopy Corp., holds a PhD from Monash University focused on FTIR spectroscopy and multivariate analysis. With over 25 years of experience in FTIR and Raman microscopy, he oversees product innovation, marketing strategy, and applications development across the company’s spectroscopy portfolio.

About Craig Prater

Dr. Craig Prater, Chief Technical Officer at Photothermal Spectroscopy Corp., holds a PhD in Physics from the University of California, Santa Barbara. With over 140 publications and 9,200 citations, he received the 2023 Coblentz Society Williams-Wright Award for advancing vibrational spectroscopy and pioneering innovations in photothermal and nanoscale measurement technologies.

This information has been sourced, reviewed, and adapted from materials provided by Photothermal Spectroscopy Corp.

For more information on this source, please visit Photothermal Spectroscopy Corp.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited (T/A) AZoNetwork, the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and Conditions of use of this website.