In its latest update, NASA reports that Dragonfly, a nuclear-powered rotorcraft designed to explore Saturn’s moon Titan, has successfully completed a series of critical development tests. These recent milestones mark significant progress toward the mission’s goal of investigating the surface of Titan for evidence of habitability and the chemical building blocks of life.

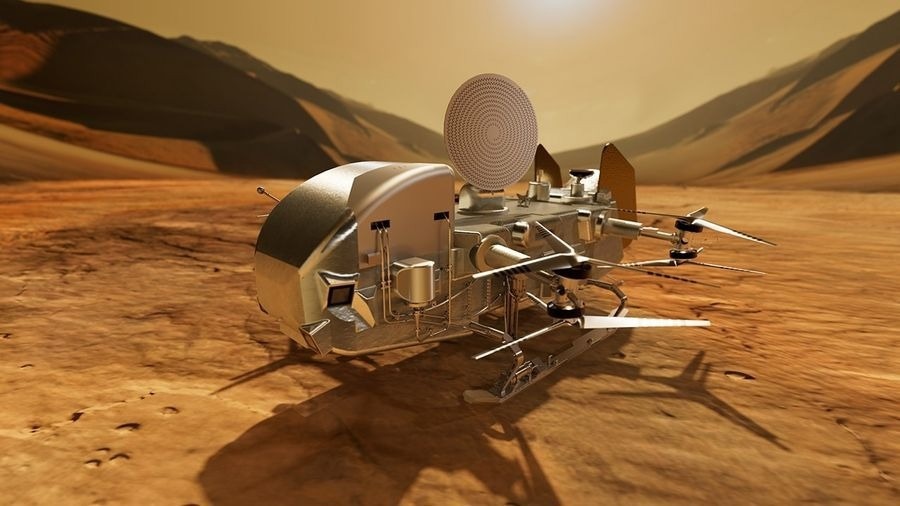

Artist's concept of Dragonfly on the surface of Titan. Image Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL

The testing campaign covered a broad range of systems, including rotor aerodynamics, thermal insulation performance, assembly of the scientific payload, and validation of flight systems and communications hardware. With each successful trial, the Dragonfly team moves closer to launch, currently scheduled for July 2028.

From Blueprint to Reality

Dragonfly is being designed and built at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. The rotorcraft will be equipped with eight rotors, allowing it to land at multiple sites across Titan’s surface and carry out scientific operations for at least three years. Its mobility is a key feature, enabling the lander to explore a wide range of terrains and environments.

Dragonfly has moved far beyond a concept on a computer screen – the components of the rotorcraft lander are being built as scientists and engineers transform this bold exploration idea into reality.

Elizabeth “Zibi” Turtle, Dragonfly’s Principal Investigator, APL

The mission’s engineering has been shaped by the unique challenges of Titan, particularly its dense atmosphere, cryogenic temperatures, and the complex demands of planetary entry, all of which have guided critical decisions around materials and systems development.

Major Milestones from Dragonfly’s Recent Testing

Aeromechanical Testing of Dragonfly’s Rotors

Ensuring the rotors function effectively is central to Dragonfly’s mission. To evaluate rotor performance under Titan-like conditions, APL and NASA engineers conducted a month-long test campaign at NASA Langley Research Center’s Transonic Dynamics Tunnel.

Using a Dragonfly model equipped with sensors, the team simulated Titan’s dense atmosphere by immersing the model in a heavy gas environment. The tests focused on measuring stress loads on the rotor arms, assessing vibration effects on both the blades and the lander’s body, and collecting data that will inform Dragonfly’s flight plans and navigation systems.

Scientific Payload: The Dragonfly Mass Spectrometer (DraMS)

At the core of Dragonfly’s scientific equipment is the Dragonfly Mass Spectrometer (DraMS), developed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. This instrument includes an ion trap mass spectrometer designed to analyze Titan’s surface for chemical compounds and biologically relevant molecules.

DraMS recently cleared its acceptance review and is now being prepared for integration with other mission components. It will soon undergo additional testing in space-like environments as part of the mission’s next development phase.

Thermal Protection: Surviving Titan’s Cold

One of the mission’s most critical design challenges has been developing thermal insulation to protect the lander in Titan’s extremely cold environment, where surface temperatures average around -185 °C (-300 °F).

Engineers at APL tested the lander’s insulation in a large environmental chamber simulating Titan-like conditions. The results confirmed that the insulation - a three-inch-thick (7.6 cm) Solimide-based foam layer - will maintain its shape and provide sufficient protection. This foam encapsulates the lander’s body and houses scientific instruments and internal components, ensuring stable operation throughout the mission.

Communications and Entry Systems

For communication, Dragonfly will rely on APL-developed “Frontier” radios, which serve as both transmitter and receiver during the journey and on Titan. These radios are compact, low-power, and capable of transmitting across a wide frequency range - ideal for the mission’s complex operational needs.

Meanwhile, Lockheed Martin has made progress in developing the aeroshell and thermal shield that will protect Dragonfly during atmospheric entry. This includes fabrication, curing, and thermal cycle testing of both the heatshield and backshell. The team has also begun static load testing and is preparing to integrate the thermal protection system, which must endure both extreme heat and mechanical stress upon arrival at Titan.

Conclusion

With several key systems now tested and validated, NASA’s Dragonfly mission is on track to begin its final integration and testing phase in January 2026. The rotorcraft remains scheduled to launch in July 2028 aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket from Kennedy Space Center.

Every major component - its precision-engineered rotors, cryogenic thermal insulation, compact radio systems, and durable aeroshell - has been subjected to rigorous testing to ensure it can endure the harsh conditions on Titan. The mission highlights the essential role that materials science and engineering play in making complex planetary exploration possible.

As Dragonfly enters its final stretch of development, it stands as a testament to how thoughtful design, thorough testing, and cross-disciplinary collaboration continue to push the boundaries of where, and how, we explore the solar system.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.