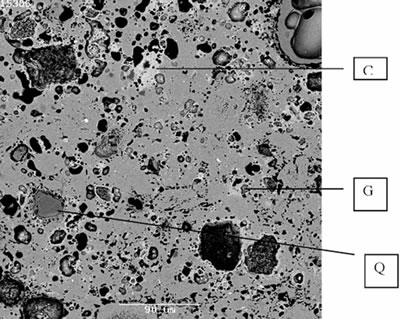

Introduction Inorganic polymers formed from naturally occurring aluminosilicates have been termed geopolymers by Davidovits [1]. Various sources of Si and Al, generally in reactive glassy or fine ground forms, are added to concentrated alkali solutions for dissolution and subsequent polymerisation to take place. Typical precursors used are fly ash, ground blast furnace slags, metakaolinite made by heating kaolinite at ~ 750°C for 6-24 h, or other sources of Si and Al. The alkali solutions are typically a mixture of hydroxide (e.g. NaOH, KOH), or silicate (Na2SiO3, K2SiO3). The solution dissolves Si and Al ions from the precursor to form a condensation reaction [2]. The OH- ions of neighbouring molecules condense to form an oxygen bond between metal atoms and release a molecule of water. Under the application of low heat (20-90°C) the material polymerises to form a rigid polymer containing interstitial water. The polymers consist of amorphous to semi-crystalline two or three dimensional aluminosilicate networks, dependent on the Si to Al ratio [1]. Their physical behaviour is similar to that of Portland cement and they have been considered as a possible improvement on cement in respect of compressive strength, resistance to fire, heat and acidity, and as a medium for the encapsulation of hazardous or low/intermediate level radioactive waste [3-6]. Although they have been used in several applications their widespread use is restricted due to lack of long term durability studies, detailed scientific understanding and lack of reproducibility of raw materials. However, if they are to be used as refractory coatings and as low temperature (1000°C) refractories, then the lack of long term durability studies will not be a hindrance. Use of geopolymers for these applications have been mentioned in the literature [7]. We have previously heated geopolymers made using Na-alkali up to 1200°C and studied their phase formation and microstructure [8]. In the present work we investigated briefly a geopolymer which was much more refractory than those studied before, based on metakaolinite precursor additions. The phase formation and microstructure are discussed. Experimental A ~ 30 g batch of geopolymer was made, consisting of 29.1 wt% metakaolinite, 4.9 wt% Ca(OH)2 (Merck, Germany), 11.0 wt% KOH (Sigma Aldrich, Australia), 44.7 wt% Kasil 1552 (PQ Corporation, Australia, composition in wt%: K2O – 21; SiO2 – 32; H2O - 47) and 10.3 wt% added demineralised water. Metakaolinite was produced by heating kaolinite (Kingwhite 80, Unimin, Australia) at 750°C for 15 h in air. An X-ray diffraction (XRD) trace showed a broad diffuse peak centred at a d-spacing ~ 0.36 nm indicative of amorphous material, and a minor amount of quartz. The original clay contained ~ 1 wt% TiO2 but the presence of a Ti-containing phase was not seen by XRD. The dry mixed powders were added to this solution and mixed by hand to ensure a smooth viscous liquid was formed. This was cast in sealed polycarbonate containers and vibrated for 5 min on a vibrating table to remove air bubbles. After holding for 2 h at ambient they were cured for 24 h at 80°C. After 5 d at ambient they were removed from the moulds and tests were performed after further 2 d. To study the effect of heating on the microstructure and loss of water and other species, the cured pastes were heated at 500, 800, 1000, 1200, 1300 and 1400°C for 3 h in an electric furnace with heating and cooling rates of 5°C /min. The density and porosity of each of the geopolymers were determined according to the Australian Standard [9] by evacuating under vacuum and introducing water to saturate the pores. The time of saturation and the immersion in water was kept to less than 15 min to inhibit reaction with water (mainly dissolution of alkali, unpublished work). All samples were analysed by X-ray diffraction (XRD: Model D500, Siemens, Karlsruhe, Germany) using CoKα radiation on crushed portions of material. Selected samples were cross sectioned, mounted in epoxy resin and polished to a 0.25 μm diamond finish and examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM: Model 6400, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) operated at 15 kV and fitted with an X-ray microanalysis system (EDS: Model: Voyager IV, Tracor Northern, Middleton, WI, USA). Results and Discussion The values of density and porosity are listed along with XRD analyses of the samples in Table 1. The open porosities of all the geopolymers increase and then decrease with increase of heat-treatment temperature. The most likely explanation is that the increase in porosity is due to the removal of water and breaking of silanol bonds at 500°C, causing the opening of pores. The porosity decrease from 800-1400°C is attributed to sintering possibly by assistance from a liquid phase. It is quite feasible to envisage the presence of a liquid phase at 800°C for a system consisting of K2O-CaO-Al2O3-SiO2, when the lowest eutectic temperature for the K2O-CaO-SiO2 alone is 710°C [10]. Table 1. Porosity and XRD analysis of Heated Geopolymers | | | 20 | 29.5 | Am (m), Q, Ca8Si5O18 | | 500 | 58.5 | Am (m), Q, Ca8Si5O18 | | 800 | 50.4 | Am (m), Q, Ca8Si5O18 | | 1000 | 37.8 | K (m), Q, G, Ca8Si5O18, L (trace) | | 1200 | 37.7 | L (m), K | | 1250 | - | distorted K (m), L | | 1300 | 30.5 | distorted K (m), L (trace) | | 1350 | - | distorted K | | 1400 | 27.6 | distorted K | Key: m=major; Am= amorphous; Q=quartz; G=gehlenite (2CaO.Al2O3.SiO2); K=kalsilite (K2O.Al2O3.2SiO2); L=leucite (K2O.Al2O3.4SiO2). The XRD traces of all the geopolymers heated up to 800°C showed a broad diffuse hump centred at d ~0.32 nm characteristic of an amorphous phase (Table 1). Trace amounts of quartz and the calcium silicate phase, Ca8Si5O18 were also present. At 1000°C, kalsilite was the major phase. Apart from the above crystalline phases, gehlenite was also observed. The SEM image for the geopolymer heated to 1000°C shows (Figure 1) a calcium silicate phase with Ca to Si ratio of 8:5 and another one close to the gehlenite composition. The EDS analysis of the matrix indicated the composition was close to that of kalsilite.

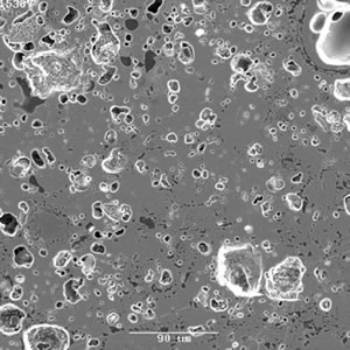

Figure 1. SEM image for the geopolymer heated to 1000°C shows a calcium silicate phase with Ca to Si ratio of 8:5 and another one close to the gehlenite composition. At 12000C the major phase was leucite and it decreased at 1250°C (Table 1). At 1250°C and above kalsilite was the major phase and no leucite was detected at 1350-1400°C. The SEM image (not shown) of the 1400°C heated sample confirmed this, but in addition it showed a trace of calcium aluminium silicate in which the Ca:Al:Si ratio was 2:1:2. The d-spacings of the kalsilite phase above 1250°C had shifted indicating the possible incorporation of another cation such as Ca (also confirmed by EDS). Similar results have been shown for a metakaolinite/K-alkali system by solid state nuclear magnetic resonance [7]. Kalsilite has a melting point of ~ 1750°C [11] and that of leucite is 1686°C [11], so both are quite refractory. Although the liquid forms at ~750°C, the presence of two refractory phases should be sufficient to make the geopolymer sufficiently refractory at 1000°C for continuous use at this temperature. Heating the geopolymer at 1000°C for 5 h did not show any slump and this is an empirical indication of refractoriness. The high porosity of the geopolymers should make them suitable for use as thermal insulators. The pore distribution at 1000°C is shown in the secondary SEM image at 1000°C (Figure 2). Refractory castables are made by mixing high-alumina cement with chamotte (calcined fireclay). When required water is added and cast to the required shape. Geopolymers could also be used similarly with chamotte. The geopolymers produced in this work had no expansion or shrinkage after curing which is also an advantage.

Figure 2. The pore distribution at 1000°C is shown in the secondary SEM image at 1000° A geopolymer made without any aggregate gave a compressive strength of ~ 80 MPa which is sufficiently high compared to alumino silicate thermal insulators used at ~ 1000°C (~ 15 MPa at 50% porosity [12]). Thermal insulators are used for lining structurally supporting refractories or as mortars in such structures. Hence, a high temperature high strength is not a pre-requisite for their use. Conclusions The geopolymers heated up to 1400°C did not show any major melting. The presence of two refractory phases kalsilite and leucite should make them sufficiently refractory at 1000°C for its continuous use. High porosity of the geopolymers should make them suitable for use as thermal insulators. Acknowledgements Authors thank Joel Davis for unpublished SEM work and Lou Vance for making valuable suggestions. References 1. Davidovits, “Geopolymers – Inorganic Polymeric New materials,” Journal of Thermal. Analysis, 37 [8] (1991) 1633-56. 2. P. G. McCormick and J. T. Gourley, “Inorganic Polymers – A new Material for the New Millennium,” Materials Australia, 23 (2000) 16-18. 3. J. Davidovits, “ Geopolymers: Man-Made Rock Geosynthesis and the Resulting Development of very Early High Strength Cement,” Journal Materials Education, 16 [12] (1994) 91-139. 4. J. Davidovits,”Chemistry of Geopolymeric Systems, Terminology,” Geopolymere ’99, Geopolymer International Conference, Proceedings, 30 June – 2 July, 1999, pp. 9-39, Saint-Quentin, France. Edited by J. Davidovits, R. Davidovits and C. James, Institute Geopolymere, Saint Quentin, France, (1999). 5. A. Allahverdi and F. Skvara, “Nitric Acid Attack on Hardened Paste of Geopolymeric Cements,” Ceramics-Silikatay, 45 [3] (2001) 81-8. 6. D. S. Perera, E. R. Vance, Z. Aly, K. S. Finnie, J. V. Hanna, C. L. Nicholson, R. L. Trautman and M. W. A. Stewart, “Characterisation of Geopolymers for the Immobilisation of Intermediate Level Waste,” Proceedings of ICEM’03, September 21-25, 2003, Oxford, England, Laser Options Inc., Tucson, USA, (2004), CD, paper no. 4589. 7. V. F. F. Barbosa and K. J. D. MacKenzie, “Synthesis and Thermal Behaviour of Potassium Sialate Geopolymers,” Materials Letters, 57 (2003) 1477-82. 8. D. S Perera, E. R. Vance, D. J. Cassidy, M. G. Blackford, J. V. Hanna, R. L. Trautman and C. L. Nicholson, “The effect of Heat on Geopolymers Made Using Fly Ash and Metakaolnite,” Ceram. Trans., 165 (2004) 87-94. 9. Australian Standard AS 1774.5-2001, “The determination of density, porosity and water absorption”, Standards Australia (2001). 10. “Phase Diagram for Ceramists”, Edited by E. M. Levin, C. R. Robbins and H. F. Mc Murdee, p. 156, American Ceramic Society, Westerville, Ohio, USA, (1964). 11. Ibid. p.157. 12. F. Singer and S. S. Singer, "Industrial Ceramics," pub. Chapman and Hall, London, UK, 1963, pp. 1284-90. Contact Details |