Aug 3 2009

Bacteria play a role in myriad industrial processes from fermentation to cleaning up environmental pollution. But floating freely in solution, the microbial cells constantly multiply, generating biomass that must be removed periodically, causing downtime. Additionally, the microorganisms cannot be localized to a specific region of interest.

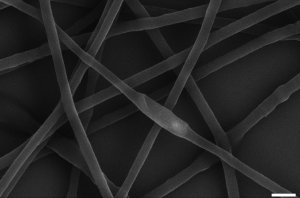

This scanning electron micrograph shows rod-shaped Pseudomonas fluorescens bacterium completely encased within the polymer fibers of an open-weave, porous hydrogel formed by electrospinning. In these bio-hybrid materials, the bacteria remain immobilized but viable for applications in biotechnology. The white scale bar in the lower right corner measures 1 micrometer."

This scanning electron micrograph shows rod-shaped Pseudomonas fluorescens bacterium completely encased within the polymer fibers of an open-weave, porous hydrogel formed by electrospinning. In these bio-hybrid materials, the bacteria remain immobilized but viable for applications in biotechnology. The white scale bar in the lower right corner measures 1 micrometer."

Now, scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and Stony Brook University have devised a way to encapsulate bacteria in a synthetic polymer hydrogel. These new, stable, bio-hybrid materials maintain the microbes' ability to exchange nutrients and metabolic products with their environment, and could find widespread applications, for example, as biosensors, catalysts, drug-delivery systems, or in wastewater treatment. The method and results are described in a paper published online by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences the week of August 3, 2009.

"In many ways, our research is trying to mimic the biofilms many microorganisms form in nature," said Brookhaven Lab materials scientist Dev Chidambaram, corresponding author on the study. "These complex and dynamic communities form when microbes encapsulate themselves in an extracellular polymer matrix, which offers them considerable protection from environmental challenges such as changes in acidity or salinity, and even antimicrobial agents.

"Our goal is to develop synthetic biofilms, in the form of bioactive materials that could be produced reliably on an industrial scale, and used or reused continuously for a range of applications. This study, which reports the generation of a very thin polymeric fibrous material in which microbes maintain their ability to function, represents a significant step toward achieving that goal."

Previous attempts to encapsulate viable bacteria in insoluble materials suffered from several shortcomings, according to the researchers. Foremost, the encapsulating materials were usually orders of magnitude larger than thin films. Because nutrients or reactants had to diffuse far into these materials to reach the microbes, activity - and microbe viability - suffered as a consequence.

To overcome these problems, the Brookhaven-Stony Brook team used a technique called electrospinning, which uses electrostatic force to produce polymer filaments. In this process, a polymer solution containing the microorganism of interest is spun to create fibers.

One challenge was developing a polymer-solvent system that would not be toxic to the bacteria. Another was achieving a structure with enough porosity to facilitate the transfer of materials such as nutrients and waste products between the microbes and their environment. Additionally, the final material must be made insoluble so it would remain intact in the watery environments envisioned for many potential applications.

The scientists met these challenges through a series of experiments to develop a method for producing their fibers. They achieved their objective - an insoluble, fibrous polymeric material in which industrially relevant bacteria were successfully encapsulated and remained viable - using a nontoxic, non-biodegradable, water-soluble polymer known as FDMA as the encapsulating agent, and by cross-linking the fibers in a glycerol solution after encapsulation to prevent the material from dissolving in aqueous environments.

Scanning electron microscope and fluorescent microscopy images reveal the rod-shaped bacteria completely encased within the tiny polymer fibers. The fibers form a mesh-like random weave with an open pore structure ideal for use as electrodes, membranes, or filters. Additional tests showed that a high percentage of the bacteria remained viable for up to several months, and their metabolic activity was not affected by immobilization. Yet the encapsulated bacterial cells do not replicate. Therefore no removal of accumulated biomass would be necessary.

The bacteria chosen for this study - from the genera Pseudomonas, Zymomonas, and Escherichia - already have industrial applications, such as fermenting glucose to produce ethanol (a key reaction of biofuel production from plant matter). Insoluble materials containing such bacteria could also be used to develop sophisticated, reusable biosensors, stable drug-delivery systems, and permeable reactive barriers for cleaning up contaminated groundwater.

In addition to Chidambaram, collaborators on the research described in the PNAS paper are: Ying Liu (graduate student) and Miriam Rafailovich of both the Advanced Energy Research & Technology Center and Stony Brook University, and Ram Malal and Daniel Cohn of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. A patent application has been filed for this method of producing biohybrid hydrogels as well as various applications. Those interested in licensing the technology should contact Dorene Price, 631 344-4153, [email protected].

This research was funded by the Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at Brookhaven National Laboratory and by the Goldhaber distinguished fellowship program at the Lab. This work is the result of a collaboration between the Brookhaven National Laboratory, Advanced Energy Research and Technology Center (AERTC), Stony Brook University and The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.