Crystallography lets scientists see materials as systems of ordered atoms, turning materials research into a predictive science. In revealing how atomic arrangements govern strength, conductivity, and stability, it established a direct link between structure and performance.

That link became measurable through the development of X-ray diffraction, driven in large part by the work of William Henry Bragg and his son William Lawrence Bragg. Their methods provided a systematic way to decode diffraction patterns and reconstruct atomic structures.

Crystallography's impact has been far-reaching. From alloy development in metallurgy to reliability engineering in semiconductors, it continues to shape how materials are designed, optimized, and used.

From Crystal Faces to Atomic Lattices

Before X-ray diffraction, unpicking crystal structure largely relied on descriptive observations. Scientists cataloged crystal shapes, symmetry, and external angles, relying on geometric rules and empirical observations to infer internal structure. Mineralogists recognized the remarkable regularity of crystals, but the atomic architecture inside them remained inaccessible.1,2

This all changed with Wilhelm Röntgen's discovery of X-rays in 1895. X-rays have wavelengths comparable to interatomic spacings, and this property allowed scientists to probe inside solids. In 1912, Max von Laue demonstrated that crystals diffract X-rays, confirming that crystals function as three-dimensional diffraction gratings and laying the groundwork for structural analysis using X-ray beams.1,2

Get all the details: Grab your PDF here!

Bragg’s Law and the Birth of X-Ray Crystallography

Image Credit: dkidpix/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: dkidpix/Shutterstock.com

The Braggs converted Laue’s initial qualitative findings into a practical framework for structure determination. Lawrence Bragg's formulation of what is now known as Bragg's law established a clear geometric relationship between X-ray wavelength, lattice spacing, and diffraction angle. Constructive interference, the law showed, occurs only when these quantities align in a precise way.2,3

Bragg's law made crystal structures solvable. Using measured diffraction angles and intensities, William and Lawrence Bragg determined the atomic arrangements of materials such as sodium chloride, zinc sulfide, and diamond.

More importantly, their approach switched crystallography into a quantitative discipline. Atomic positions could now be refined, tested, and linked directly to physical properties like density, symmetry, and bonding.2,4

Understanding Bonding, Defects, and Phases in Metals

Once researchers could determine atomic positions, crystallography began to guide the design and control of metallic materials. X-ray diffraction techniques uncovered that many metals exhibit simple close-packed or body-centered cubic structures. Subtle changes in stacking sequence, substitutional or interstitial atoms can strongly affect mechanical and chemical behavior.5,6

Today, high-energy X-ray diffraction microscopy extends this capability into three dimensions, mapping grain orientations and internal strains inside bulk metals at micrometer resolution. These measurements capture how dislocations, grain boundaries, and phase transformations evolve under load or heat, enabling more precise control over alloy composition, heat treatment, and processing routes.5,6

Crystallography in Semiconductor Design and Thin Films

Crystallography has also established a critical foundation for semiconductor technology, where the performance of devices depends on precise control of lattice perfection and epitaxial relationships.

X-ray diffraction has identified the dominant crystal structures of elemental and compound semiconductors and clarified how dopants integrate into host lattices. It has also provided quantitative strain measurements in heterostructures and multilayer systems.5,7

Modern X-ray techniques support the growth and characterization of thin films, quantum wells, and superlattices by resolving layer thickness, interface roughness, and lattice mismatch with high accuracy. These parameters are critical for tuning electronic band structures, managing defects, and improving junction quality in microelectronic and optoelectronic devices.5,7

Nanomaterials, Defects, and Coherent Imaging

As materials science moved to the nanoscale, the field of crystallography evolved from traditional single-crystal measurements to techniques capable of resolving local structures, strains, and defects in nanoparticles and complex microstructures.

High-energy X-ray diffraction microscopy, along with similar methods, allows researchers to map orientation fields and strain tensors in three dimensions, even in polycrystalline samples that experience complex loading histories.5,6,8

Bragg coherent X-ray diffraction imaging further enhances this capability by enabling the reconstruction of real-space images from coherent diffraction patterns, which can reveal dislocations, facet strains, and defect networks with nanometer resolution.

These advanced methods provide engineers with valuable insights into how materials, such as catalysts and battery particles, behave under real operating conditions. This gives a better understanding of the relationship between defect structures and important properties like catalytic efficiency, electrochemical stability, and ferroic switching behavior 6,8

Saving this article for later? Grab a PDF here.

Broader Impact Across Materials Science

X-ray diffraction remains one of the most versatile non-destructive tools in materials research. Powder diffraction supports phase identification and quantitative analysis across ceramics, polymers, and composites, while reciprocal-space mapping captures texture, residual stress, and preferred orientation in processed materials.5

Recent advancements in X-ray sources, detector technology, and data analysis pipelines have significantly improved time resolution and sensitivity. Operando and in situ crystallography now track crystallization, phase transitions, and degradation as they happen, helping researchers refine growth models, assess long-term stability, and design materials for demanding environments.5,6

Evolution from Knowledge to Predictive Design

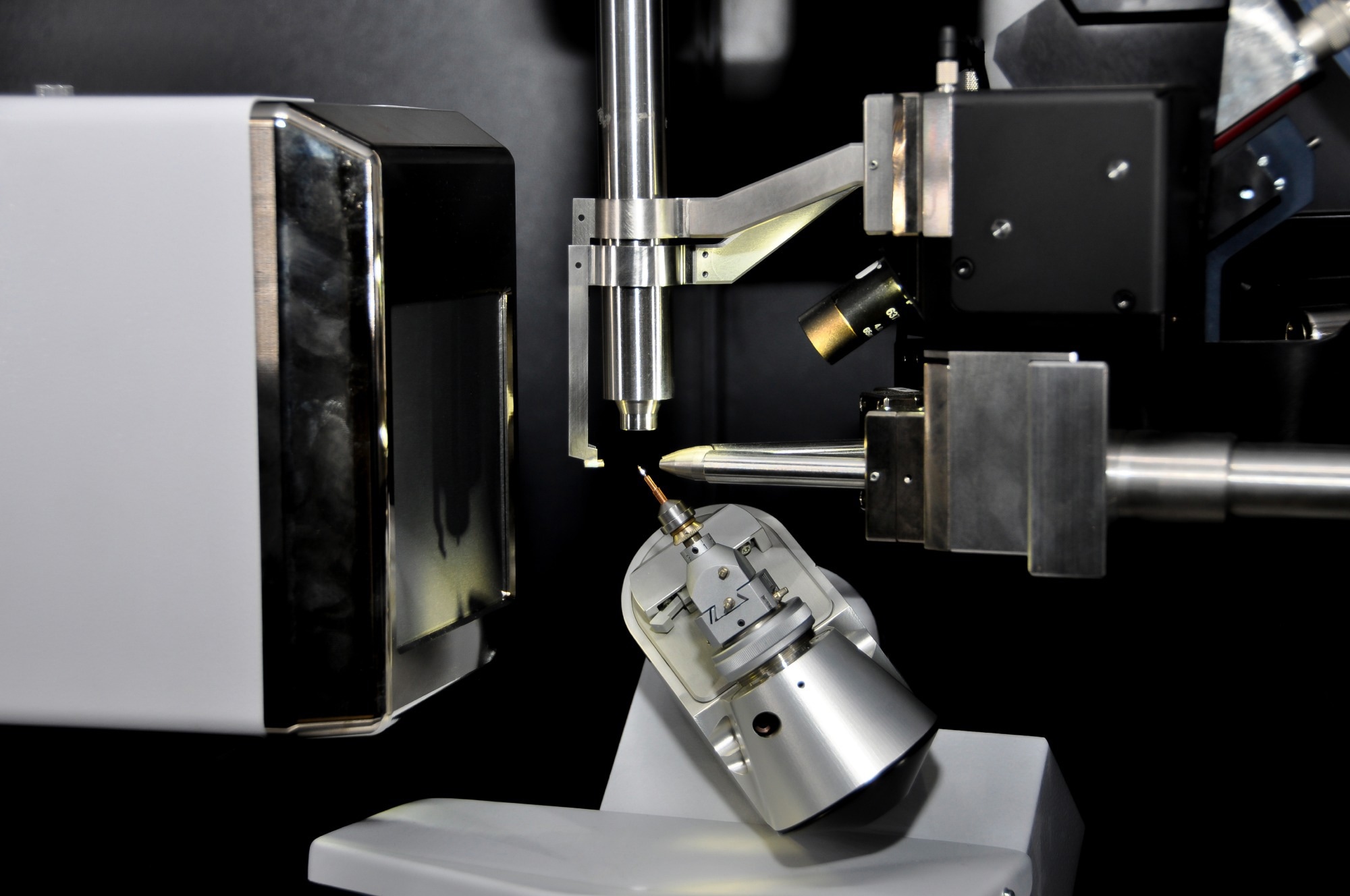

Image Credit: Isuaneye/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Isuaneye/Shutterstock.com

The evolution of crystallography shows how the ability to see atomic arrangements drives predictive materials design. X-ray diffraction connects structure to properties in a quantitative way, such that lattice parameters, symmetry, and defect populations become design variables rather than unknowns.3,6

Today, crystallographic data underpin computational materials science, providing structural inputs for simulations and benchmarks for predicted phases.

From the Bragg’s first diffraction experiments to modern coherent imaging, understanding materials at the atomic level is what makes systematic engineering possible.1,5,6

References and Further Reading

- Crystallography: How discovering crystal structure gave meaning to matter. Institute of Physics. https://www.iop.org/explore-physics/big-ideas-physics/crystallography

- X-Ray Crystallography Is Developed by the Braggs. EBSCO Research Starters Home. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/x-ray-crystallography-developed-braggs

- Pope, C. G. (1997). X-Ray Diffraction and the Bragg Equation. Journal of Chemical Education, 74(1), 129. DOI:10.1021/ed074p129. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ed074p129

- Deschamps, J. R. (2010). X-Ray Crystallography of Chemical Compounds. Life Sciences, 86(15-16), 585. DOI:10.1016/j.lfs.2009.02.028. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0024320509000952

- Omori, N. E. et al. (2023). Recent developments in X-ray diffraction/scattering computed tomography for materials science. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 381(2259). DOI:10.1098/rsta.2022.0350. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/rsta/article/381/2259/20220350/41286/Recent-developments-in-X-ray-diffraction

- Bernier, J. V. et al. (2020). High-Energy X-Ray Diffraction Microscopy in Materials Science. Annual Review of Materials Research, 50(1), 395–436. DOI:10.1146/annurev-matsci-070616-124125. https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-matsci-070616-124125

- Jubair, H. et al. (2025). Exploring the Practical Applications of Crystallography and Semiconductor Materials: Current Advances and Future Prospects. Authorea. DOI:10.22541/au.173956833.32066019/v1. https://www.authorea.com/users/820892/articles/1268686-exploring-the-practical-applications-of-crystallography-and-semiconductor-materials-current-advances-and-future-prospects

- Yang, D. et al. (2022). Refinements for Bragg coherent X-ray diffraction imaging: Electron backscatter diffraction alignment and strain field computation. Journal of Applied Crystallography, 55(Pt 5), 1184. DOI:10.1107/S1600576722007646. https://journals.iucr.org/j/issues/2022/05/00/te5099/index.html

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.