Adaptable molecular devices that function as memory units, logic gates, processors, or electronic synapses have been achieved without silica.

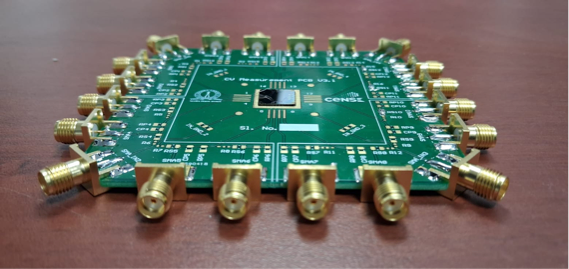

The device setup. Image Credit: CeNSE, IISc

The device setup. Image Credit: CeNSE, IISc

Researchers at the Indian Institute of Science created the device. Their study was recently published in Advanced Materials.

Silica is often used in electronics, but for health and environmental reasons, researchers have been seeking an alternative for some time. Additionally, current leading molecular electronics, which are primarily made using oxide materials and filamentary switching methods, act as designed machines that simulate learning, rather than as matter that inherently possesses it.

This new study aims to tackle both challenges at once.

Engineers and scientists at the Centre for Nano Science and Engineering (CeNSE) in India have developed these minuscule molecular devices that can be adjusted to perform various functions.

It is rare to see adaptability at this level in electronic materials. Here, chemical design meets computation, not as an analogy, but as a working principle.

Sreetosh Goswami, Assistant Professor, Centre for Nano Science and Engineering, Indian Institute of Science

This adaptability is enabled by an exact chemistry. The team synthesized 17 meticulously designed ruthenium complexes and examined how small changes in molecular geometry and ionic environment influenced electron behavior.

By precisely adjusting the ligands and ions surrounding the ruthenium molecules, the researchers demonstrated that a single device can display various dynamic behaviors – such as switching between digital and analog – across a broad spectrum of conductance values.

What surprised me was how much versatility was hidden in the same system. With the right molecular chemistry and environment, a single device can store information, compute with it, or even learn and unlearn. That’s not something you expect from solid-state electronics.

Pallavi Gaur, Study First Author and PhD Student, Centre for Nano Science and Engineering, Indian Institute of Science

Understanding this finding required rigorous theoretical evaluation. The team developed a transport framework based on many-body physics and quantum chemistry, capable of predicting function from molecular structure.

This allowed them to map how electrons move through the molecular film, how individual molecules undergo oxidation and reduction, and how counterions rearrange within the molecular matrix, together governing the switching and relaxation dynamics and the stability of each molecular state.

Importantly, the distinct adaptability of these complexes enables the integration of both memory and computation within the same material. This could lead to neuromorphic hardware where learning is encoded directly into the material. The team is currently working on integrating these materials onto silicon chips, with the goal of developing future AI hardware that is both efficient and inherently intelligent.

“This work shows that chemistry can be an architect of computation, not just its supplier,” says Sreebrata Goswami, Visiting Scientist at CeNSE and co-author on the study who led the chemical design.

Journal Reference:

Gaur, P., et al. (2025). Molecularly Engineered Memristors for Reconfigurable Neuromorphic Functionalities. Advanced Materials. DOI: 10.1002/adma.202509143.